HELLO FRIENDS!

In this wild moment, as we’re all hunkered down, I’ve decided to post here the responses to the books I’ll be teaching in my Longer Fictional Forms class at Bryn Mawr College. It’s a novel-writing class, but when we’re not workshopping, we’re reading a book a week. So far we’ve read: Justin Torres WE THE ANIMALS, Marilynne Robinson’s HOUSEKEEPING, Akhil Sharma’s FAMILY LIFE and Toni Morrison’s SULA. I’d encourage you to read them.

Meantime, I’ll post a long response to each of our next texts here each week. Up now are our final two readings of the semester:

Italo Calvino’s Invisible Cities &

WG Sebald’s The Emigrants

It might seem like a strange pairing, but I decided as soon as I started doing these written comments for you that rather than separate readings of Sebald and Calvino, I’d comment on them together. On the face of it, they’re as different from each other, stylistically speaking, as any two writers could be. Calvino digs deep on the confluence of science and fantasy, on the confluence of the mundane and the strange. Invisible Cities in particular is comprised of short, 1-2pp stories that at times are essentially prose poems. Sebald by contrast is our bard of post-World War II memory, of the metaphysics of trauma and ghostliness, of the confluence of fiction and memoir/personal essay, always toying with what he knows and what we know, what we both don’t and can’t. He writes in long, dependent-clause laden lyrical prose, paragraphs that can string on for five, ten pages.

From there, though… I think their projects are much the same. Both were abiding and capacious students of the history of literature and the history of history. Both wrote in their native languages—Calvino in Italian, Sebald in German—but had strong English, and the translations of their work were avowedly collaborative, with William Weaver and Michael Hulse, respectively. Sebald even spent most of his adult life teaching at the University of East Anglia, now the most prominent creative writing department in the UK.

What I want to talk about here is the way that they are two of our major 20th century longer prose geniuses who use the specificity of their prose, the precision of objects, the precision of nouns—proper nouns, in particular—to open the door to the fantastic, the metaphysical, the world beyond our vision, our memory, our existence.

In Six Memos for the Next Millennium, Calvino sets out this question of objects, of things, in fiction much better than I could:

I would say that the moment an object appears in a narrative, it is charged with a special force and becomes like the pole

of a magnetic field, a knot in the network of invisible relationships. The symbolism of an object may be more or less explicit,

but it is always there. We might even say that in a narrative any object is always magic.

“In a narrative, any object is always magic.” That sounds exactly right to me, and I think its force in Calvino’s work always rests on the acceptance that the harder we drive toward that ineffable magic, the more we owe deference to our description of, our attention to, the tangible, visible world. (I can’t help but think here, while discussing a book with the word “invisible” in its title, of Conrad’s famous claim that as a writer, “my job is to make you see—to render as accurately as possible the visible world—and that is everything.”).

But Calvino in particular does a lot of his seeing through his imagination, and it’s that pairing that at least for me puts him at the front of the list of 20th century writers along with Virginia Woolf, Kafka, Faulkner, Beckett, Morrison. The vivid images he so quickly crafts for us in all his work, but in particular in IC, are so lasting I think of them, say, once a week. I’ll hone in on just one or two of them for our purposes here, starting with my favorite—“Trading Cities 4,” the city of Ersilia. In each of his cities Calvino balances the impermanence of any given city over time with its inherent tangibility. With Ersilia he does so with the image of a web of strings. “In Ersilia, to establish the relationships that sustain the city’s life,” he writes:

The inhabitants stretch strings from the corners of the houses, white or black or gray or black-and-white according

to whether they mark a relationship of blood, of trade, authority, agency. When the strings become so numerous that

you can no longer pass among them, the inhabitants leave: the houses are dismantled; only the strings and their supports

remain.

In part I want to talk about this city because of how beautiful I find it—but for our purposes here, it also strikes me as a great exemplar of Calvino’s genius with things. Look at how simply and quickly he makes his strings tangible here. They’re strings. He grants them colors-- “white or black or… black-and-white”—and the specificity of their stretching “from the corners of houses.” Before we even have the chance to abstract these strings, to read them as symbol, Marco Polo’s description flies to abstractions on its own, imaging “relationships of blood, of trade, authority, agency.”

I think what I want to say here is that the speed and specificity with which Calvino places these strings on the page, and then makes something of them, is remarkable. We have no time to sit with their physicality, to start reading them as text, before they quickly become abstractions—and then “the houses are dismantled.” No sooner did the objects become objects than the very edifices—fictional edifices, but still—are whisked away. These are truly “magic objects,” but they are primarily, first and foremost, objects. It allows us to feel a kind of fractalated view of these cities, which are so tangible and impermanent in Calvino’s imagining of them.

Before turning to Sebald, I’d also just like to point out briefly how each city is intermingled with the others in a variety of ways. There’s the obvious fact that given that Ersilia is “Trading Cities 4,” it is tied to the Trading Cities stories that come before and after. But even just the story that proceeds it, “Thin Cities 5,” is linked by image. It opens with Polo’s narration: “Now I will tell you how Octavia, the spider-web city, is made. There is a precipice between two steep mountains: the city is over the void, bound to the two corners with ropes and chains and catwalks.” Again, this is a city defined by its ropes—this time a “spider-web,” an image so familiar it evokes an everyday object from our empirical experience. It lends almost a sense of verisimilitude to the piece before whisking that sense away. We learn that the “foundation of the city [is] a net which serves as passage and as support.” But then we learn by the end of the three paragraph story that “Suspended over the abyss, the life of Octavia’s inhabitants is less uncertain than in other cities. They know the net will only last so long.” Again: the evanescence of our living together, the impermanence of even our most trusted structures, is so playfully and clearly and weirdly evoked.

So it would be easy to read closer and closer, more and more into IC’s networks (as plenty of critics sure have) but I think the lone thing I’m trying to draw out here is how Calvino grants us access to the intangible, the evanescent, the metaphysical and the magical, through granting us very straight-forward tangible objects, not the opposite. He does not ask us to “read” closely his objects like we were taught to in primary school, to interpret. We don’t read into; we grapple with, feel, touch. The things in Calvino’s worlds are things. The worlds are worlds. The question is what he does with them. The magic he works isn’t a magic he asks of us—it’s up to him to make the magic.

*

The objects in The Emigrants come to us just as tangibly as in Calvino. At times even more directly. Sebald is also obsessed with cities, as TE is a novel about what the Europeans traumatized by the events of WWII, and forced to leave their home cities for others. (It’s very much worth reading his long lecture “On the Natural History of Destruction,” the first full-fledged unveiling of the history of the Allied area-bombing of German cities in 1944-1945, in which more than 90% of Germany’s cities were bombed to essential destruction). In this book, we move between British cities, to Ithaca in the US and the original Ithaca in Greece, to North Africa and the Maghreb, to Jerusalem and Yemen.

But Sebald’s genius is to stick with individual characters, and to show them amid their stuff and their memories. The Emigrants is essentially one huge profusion of proper nouns, of things, so that it feels to me not unlike my Hungarian grandparents’ living room on Long Island, which was a kind of emetic of tchotchkes from the Budapest they too were forced to leave during WWII. No coincidence there. Emigrants carry with them the small objects they’re able to carry, give names to the things they find when they arrive, in order to retain what memory they can.

And so we get moments loud and quiet. Take the opening of the book. Just as we’re reading first of two British cities in Norfolk and Hingham, we encounter our first photograph in the novel, this one depicting a huge oak tree atop whose huge roots system sit gravestones. We infer the bodies interred between the subterranean roots and the above-ground markers. The photo is itself an object, a thing, depicting an object, a tree, which is a living thing. Sebald’s is a complicated internecine schema, not unlike Calvino’s. It masquerades as something much more mundane—we are forced to watch Dr. Selwyn’s slides from a vacation abroad at the middle of the story, the only old-people-forcing-us-to-watch-slides scene I know of in all of literature. It should be the most mundane of all activities— and would be, if only a dead body wasn’t about to arise from seventy years stuck in a glacier. “And so they are ever returning to us, the dead,” we learn on the last page of this opening section. If we’re reading closely enough, we might head back to page one and start to fear the bodies in that country graveyard might come back to us to.

Before we get too far into the ways that The Emigrants uses its images and objects to bring off a kind of metaphysical ghost story whose equals we might only find in The Turn of the Screw and Shirley Jackson, I do want to linger over one proper-nouning in the “Selwyn” section. When the Sebald narrator and his Clara first come to the property, Dr. Selwyn introduces them to his three horses, Herschel, Humphrey and Hippolytus. We learn later in the story that Dr. Henry Selwyn’s later life has been upended by a secret he’s kept—that he is a Lithuanian Jew who immigrated to the UK. “My confidence was at its peak,” he says, “and in a kind of second confirmation I changed my first name Hersch into Henry, and my surname Seweryn to Selwyn.” We flip back to realize all at once that Hersch, short for Herschel, has named one of these horses after his birth name. Adam’s first act was to name the animals, and by doing so to gain propriety over them. The objects in The Emigrants shimmer with their own magic, a magic of near Ovid-like ability to transform, or to constrict. Slap a capital letter on a horse or a city or a person and suddenly we infer propriety, ownership. It’s the physical world we assume holds the deed.

There’s such an intense patterning in Sebald, as James Wood points out, that we could easily spend the rest of our time thinking about Sebald’s things/objects by finding the renamings, or even just the trinities—from the three times Nabokov shows up as “butterfly man” to the three fates Sebald comes upon in a photo on the book’s final pages—“I wonder what the three woman’s names were—Roza, Luisa and Lea, or Nona, Decuma and Morta, the daughters of the night, with spindle, scissors and thread.” If you read enough, all trios of women might become the fates; travel enough and all Ithaca’s are at once home to Cornell and to Telemachus.

But I want to land here on my own favorite part of The Emigrants, the “Ambrose Adelwarth” section. It’s the longest and most involved, and to my mind Uncle Ambrose is the most complicated character in all of Sebald’s work. He is a man ravaged by loss of love, by a culture that first refuses to accept his religion and then his homosexuality, ravaged by the ECT he’s been administered in New York, and which essentially takes everything from him. The first thing I’d like to point out is that this is also the section in which Sebald’s ruse over the objects he places in photos is most elaborate. We’ve learned over the years that while many of the photos are pictures of his family, instances like Ambros’s “agenda book” on p127 are fabrications. It’s a journal he found at a thrift shop, and the illegible printing we see later is scribble Sebald himself put in. The beautiful, spare narrative of Ambros’s we get later is a fiction Sebald has concocted, going as far as to invent continent-hopping dreams. Uncle Kasmir tells us that “Uncle Adelwarth had an infallible memory, but that, at the same time, he scarcely allow himself access to it.”

The passage from this part that sticks with me most, and which feels most on point to our discussion of objects, comes when we’re in Ambros’s diary itself. Upon a month near the Bosporus he writes: “Like Death itself, the cemeteries of Constantinople are in the midst of life. For every one who departs this life, they say, a cypress is planted. In their dense branches the turtle doves nest. When night falls they stop cooing and partake the silences of the dead.” As I say, this is ultimately a kind of ghost story—The Emigrants uses the word “ghost” and its synonyms literally dozens of times—but which always appeals to the empirical to bring off the way Sebald wants to realign how we use that word, that concept. From death the cypress grows, in a book obsessed with describing and cataloguing trees.

Early on in his lecture on “Lightness,” Calvino himself writes: “For Ovid, too, everything can be transformed into something else, and knowledge of the world means dissolving the solidity of the world. And also for him there is an essential parity between everything that exists, as opposed to any sort of hierarch of powers or values.” It’s just that kind of equality both of these writers strive for—no hierarchy of things, or of character.

So this I suspect is the genius we can steal from these otherworldly geniuses. Push hard enough on the real world, grant it its names with their capital letters, it’ll go poof with a feeling of magic. This is what I get most in the final lines of “Ambrose Adelwarth,” some of my favorite in all of literature, a fabricated diary Sebald has imagined, and which almost sounds like a page out of Invisible Cities:

Memory, [Ambros] added in a postscript, often strikes me as a kind of dumbness.

It makes one’s head heavy and giddy, as if one were not looking back down the

receding perspectives of time but rather down on the earth from a great height,

from one of those towers whose tops are lost to the view in the clouds.

A reading of F. Scott Fitzgerald’s edits from TRIMALCHIO: AN EARLY DRAFT to THE GREAT GATSBY

So this is always the high point of the semester for me, what I think of as the centerpiece of this class: getting to think through how to talk tangibly about novel revision, and getting to do it with the best material lesson I know: the changes Fitzgerald made between Trimalchio, the draft of Gatsby he sent to Maxwell Perkins in 1924, and the final of the novel that appeared the following year.

It’s a masterclass in novel writing, in revision, in listening to your reader/editor and in both trusting and listening to yourself.

I want to start out by taking probably too far a step back. As you guys know, I think it’s useful at times just to stand back and name a problem, without worrying too much about solving it, allowing your subconscious to do that work. And given that we’re in a workshop here, I often like to step back and name some of the problems with the workshop model itself (a model that started at Harvard and then Iowa in the late 1920’s, not coincidentally right around the time The Great Gatsby was published). Two of the biggest self-apparent issues I think reading Trimalchio closely can help address are these:

--First, that the workshop tends to lend itself to workshopping only short stories.

--Second, that workshop isn’t very good at tackling the order of a story/novella/novel.

The former is the louder of the two, and it’s the one this entire course grapples with at every turn. A decade ago when I first conceived of the class, I asked: ok, so can we do a novel-writing course in a semester? And what would it look like? And having read this revision of Gatsby, I felt I’d found a centerpiece that could make us feel we were on solid ground. By pushing as far as we can in drafting, by taking as much time as possible to read read read short novels, at a pace of one a week, I think for the weeks here we can get a solid, initial start or draft down. And of course I’m so impressed by how you guys have done so, already. We can do a novel workshop as long as we loosen some of the strictures of the original workshop model, I think: having workshop itself be less about critique than just describing work back to the writer; and taking the onus off of the idea of “finishing” a draft in the space of a semester. Both of those seem like artificial aspects of the endeavor to me, anyway.

But I think maybe the more important thing Trimalchio (from here on out T) allows us is the latter: it allows us to see, shockingly clearly, how much order can effect the way we read a book. (I’m relatively convinced this is true even in a short short story, but it’s more a feature of the novel than any other form). One of the coolest things about Trimalchio is how it’s kind of bookended by pages that won’t be changed in Gatsby (from here on out GG) at all. It still opens with those iconic paragraphs starting, “In my younger and more vulnerable years my father told me something that I’ve been turning over in my head ever since. ‘When you feel like criticizing anyone,’ he said, ‘just remember that every body in this world hasn’t had the advantages that you’ve had.’” How fresh and topical that admonition feels almost a hundred years later, the way we talk about privilege. And the other bookend, the final pages are essentially unaltered from draft to draft. Nick still stands imagining New York denuded of its modern buildup, and sees “Its vanished trees… that had once pandered in whispers to the last and greatest of all human desires” until he comes “face to face for the last time in history with something commensurate to his capacity for wonder.”

It’s hard in these last pages not to read through the scrim of our current pandemic-empty moment, photographs of Sixth Avenue empty of people and cars, Vatican Square and the rest. It’s not Nick stripping New York of New York, but there is a sense of the prophetic always in Fitzgerald’s voice, a sense that it’s at once of the moment and entirely lasting, appealing to the abstractions and to the metaphysical in our readerly minds.

Before turning away from this digression I’d be remiss not also to mention that it felt impossible not to read both versions this time through with pandemic in mind. It strikes me that the 1918 Spanish Influenza had torn through the globe not five years before Fitzgerald began writing—and there’s not a whiff of it in the book. Some of this is almost certainly because the massive death toll of World War I, which is very much in the text, loomed larger in mind. We can’t really compare what the millions of deaths from influenza must have felt like on the heels of the millions of deaths from world war. (I also just happen to be reading Siddhartha Mukherjee’s masterful nonfiction book Emperor of All Maladies: a Biography of Cancer, right now, and he details how American life expectancy moved from 43 years to closer to 70 between 1900 and 1950, a fact that’s hard to fathom, let alone incorporate into thinking about a novel). But this is all to say that maybe some of that Lost Generation opulence we’re all taught to read into GG in high school, and treated to visually in Baz Luhrmann’s film version, is about a natural and ostentatious embracing of the sanctity of life after so much death, rather than some kind of facile cultural critique. I’d look forward to something like it after all this time inside, should we be so lucky.

*

But the idea here was to think about order, and sequencing, and how shifting the order of the release of information through drafting a novel can wholly change our reading (and how integral it is to the completion of a novel to give time over to that ordering).

To me the shifting of the release of Gatsby’s background from T to GG is the best example I’ve ever found of a major writer doing so. The vast majority of major changes to the novel come in FSF’s revisions of Chapters VII and VIII, and by far the most significant come in his dealing with how we learn about Gatsby. In his famous editorial letter to FSF, Perkins writers that “the reader’s eyes can never quite focus” on Gatsby in T. The lesser writer would spend his time grinding out description after description of the character. But as you’ve heard me say a million times, this relates back to that great thing Neil Gaiman includes in his rules for writing—something along the lines of, Your reader is almost always right when they say there’s something wrong with your draft, and they’re almost always wrong when they tell you how to fix it.

So what FSF perceives, I think, is that the issue with Gatsby is less his physicality (though he addresses that, too) than the dramatic way his background is revealed to us, and when. In T, we get it all at once, right at the top of Chapter VIII. We’ve learned almost nothing about him so far, and then starting all at once on p117, we learn everything about Dan Cody, G’s love for Daisy, his time in the war, etc. But it’s almost wholly static: Nick and Gatsby sit talking. It’s not dramatized.

We’re reading Calvino next week, and this lovely idea from his Six Memos for the New Millennium, on the quality of “quickness” in literature, feels apt here. He considers that the two qualities the novelist needs are those of Vulcan’s “craftsmanship” and Mercury’s “speed,” and he writes:

Vulcan’s concentration and craftsmanship are needed to record Mercury’s adventures

and metamorphoses. Mercury’s swiftness and mobility are needed to make Vulcan’s

endless labors become bearers of meaning. And from the formless mineral matrix, the

gods’ symbols of office require their forms: lyres or tridents, spears or diadems.

Which is to point out that FSF’s form here is the novella. GG clocks in at under 50K words, and its author lamented that fact after the book initially sold poorly. But for our purposes it’s important that if GG is one of the most perfect American novels, it is in part because of its brevity. “The novella is a horse,” Calvino writes earlier in that essay “Quickness,” “a means of transport with its own pace, a trot or a gallop according to the distance and the ground it has to travel over.”

And to come to the point here finally: there’s no trot or gallop to the version of Gatsby’s background in Chapter 8 of T that maunders over six late pages of the book. After reading Perkins’ letter he sees that that’s the issue—Gatsby is obscured by an issue of order, drama and sequencing: we can’t see him when he’s obfuscated by the stand-still static of scene. And so what FSF is simple and brilliant: he just peppers almost all of the narrative exposition from those ~6pp throughout the final draft. In a somewhat stagnant moment when Jordan Baker wants to talk to Nick in the “Owl Eyes” party at Gatsby’s, now she learns some of Gatsby’s background. She tells Nick. It makes her more nefarious too, a gossip.

And here are the two things I think I want to pull out of this most clearly in what it shows me about drafting and revising a novel. I’ll end with them, as I think they’re all important and deserve to stand on their own, lone oak trees in this digressive field of acorns:

--The lesson of T is NOT THAT FITZGERALD SHOULDN’T HAVE WRITTEN AN INFERIOR DRAFT. The idea here isn’t, Do better in a first draft. The idea isn’t: don’t write T, write G. The idea is get it all out. Spill it on the page. WRITE T. I suspect after dozens of reads of both T & GG that FSF himself didn’t know some of what he learned about Gatsby in those late pages—the full story of his five months at Oggsford, some of his feelings for Daisy. But he discovered them on the page (“how do I know what I write until I see what I say,” as EM Forster’s old lady has it). By the time he’s finished the book, written “and so we beat on…” he’s so excited he thinks, I’VE DONE IT! (Fuck, who wouldn’t after writing those last three pages of perfect prose?) And he immediately hits send, forgetting he was gonna smooth all that stuff over. It takes his subtle reader in Perkins just to subtly say, Back to it, one more time. But again: WRITE THE MESSY DRAFT, THEN FIGURE OUT WHAT’S WRONG. And often what’s wrong isn’t the prose, the style. It’s the order.

--And the second lesson, the lesson of order, is: be bold. Make a whole bunch of clay so you can figure out what you want to sculpt it into. Just move pieces around whole-cloth. FSF doesn’t go through and rewrite, reconceive of the ideas he found in T. He cuts and pastes them intact. He found not just facts about Gatsby but language—“Gatsby… sprang from his platonic conception of himself,”; “his heart was in a turbulent riot”—and so, even without the benefit of Microsoft Word, he cuts and pastes it all. It’s the same material, the same sentences. They’re just earlier, they’re meted out throughout the book. And suddenly it all… works. And so we beat on…

Sigrid Nunez’s THE FRIEND

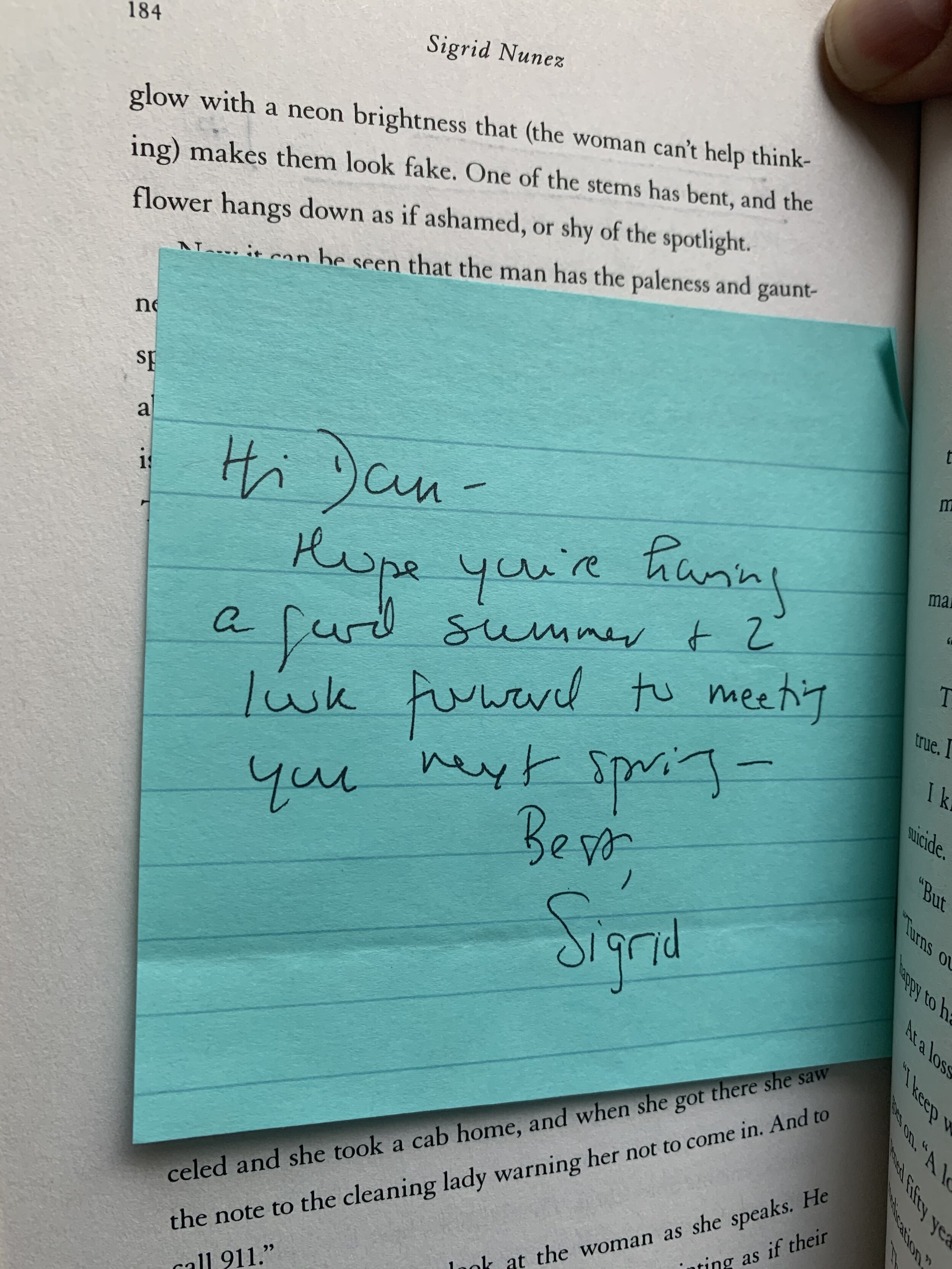

Well we’re all working on the fly here. Sigrid Nunez was meant to come visit us for the day, and we had the luck of reading her beautiful novel THE FRIEND, last year’s National Book Award winner for fiction, as a result. But global pandemic had other plans, so all we have is this nice note about how we were all going to see each other. Ugh. Well, we’ll see her soon enough. I also like to teach at least one novel that’s wholly new to me each semester, so I can read fresh along with you. So I’ll start with the context that I’m really really not lecturing here—just trying to pull the same kind of ideas you all are from my read, as opposed to some of what we’ll do with, say, the Fitzgerald, which I’ve now read like 20x (yikes), and have some solid ideas about.

With that in mind, I actually want to start here by quoting from another of my favorite contemporary fiction writers, Lydia Davis, from a major essay of hers, “Fragmentary or Unfinished.” The Friend is a novel about a woman who takes over care of a friend’s dog after the friend commits suicide, but it’s also a novel built of fragments, and a novel about grief. So here’s Davis, and I hope it’s OK I quote from her at length. “The word fragment implies the world whole,” she writes:

A fragment would seem to be part of a whole, a broken-off part of a whole. Does it also imply, as with other broken-off pieces, that enough of them would make a whole, or remake some original whole, some ideal whole? Fragment, as in ruin, may also imply something left behind from a past original whole. In the case of Hölderlin’s Fragments, they are the only parts showing of a madman’s poems, the rest of which are hidden somewhere in his mind; or the only parts showing of a logical whole whose logic is unavailable to us, fragments that seem whole—for there is only a thin line between what is so new to us that it changes our way of thinking and what is so new to us that we can’t recognize it as a coherent thought or piece of writing, can’t see the connections the author sees, or even sense that they are there. Or fragments that seem to him to make a whole and to us, eventually, also to make a whole, though from a different angle.

[OK I know this is getting long but the next graph is all important so bear with me/Lydia.]

Or, as with Mallarme’s fragmentary poems for his dead son, the fragment is something left from some projected whole, some future whole (i.e., fragments destined one day to be pieced together with other elements to make a whole): or the fragments of ideal poems shattered by grief; fragments comparable to the incoherent utterances of voiced grief; inarticulateness being in this case the most credible expression of grief: no more than a fragment could be uttered, so overwhelming was the unuttered whole. In the silences, the grief is alive.

“Fragments… shattered by grief” actually seems like not the worst subtitle for The Friend. While there are lots of elements of Nunez’s book that allow it to cohere—and I’d like to get to that much more directly in the latter part of this comment— it is defined, I think, by the way it expresses grief through fragmentation. There are moments throughout that feel almost essayistic: long movie synopses, book synopses, piles of quotations from favorite writers from Joy Williams to Wittgenstein to Simone Weil to Lady Gaga (!), letters, even just lists of verbs. There’s the immediate move to the second-person address to the friend who has passed—but there’s a lot of first person, too. Late in the novel, Nunez even addresses that 1p directly: “writing in the first person is a known sign of suicide risk,” she writes with not a small does of gallows humor. There’s lots of sly dark humor throughout The Friend. And excepting the ending, which throws a bit of a wrench in the gears and which we should put aside for now (and maybe forever), I think it’s this sense of essayistic fragmentation that defines so much of what I want to steal from this novel.

So often when we’ve been pounding pounding pounding away at a novel draft, there’s a move, especially late in drafting, when we start to want to start tying things together, to making meaning. As Nunez has her narrator herself says late in the book: “I’d sit there and ask myself, what was I hoping to do with all this violence…. Organize it into some engaging narrative?” The beauty of her approach here is that she finds a form that allows her not to start forcing narrative onto the poetry, the facts and the fragments. Not to suggest that this is part of a whole, but that the fragments are the thing itself. Narrative implies causation—as EM Forster famously puts it, “the king died then the queen died of grief”—and I think the only real causal link she wants to make really anywhere here is, Because the Friend died, the narrator takes on Apollo. And then later, Because Apollo is a Great Dane, he’ll die in a couple years (more on that later).

Instead there are lists, and letters, and often a kind of what I like to think of as rhyming of scenes that rhyme in a way that makes meaning. The example of this that I think stuck with me most comes when, early on, the narrator notes that she often notices people on the subway, only later to realize they’re going to the same literary event as her. (Quick aside—if it’s not a narrative, I guess she’s not a narrator? So let’s call her the fragmentor? Fragment Collector/FC? Fragmenter?) Halfway through the book we see this recur—on her way to a book festival in Brooklyn (guessing it’s the Brooklyn Book Festival, but she doesn’t say), she sees a couple on the train, and then “in line just ahead of me” at the bar. (Amy Hempel has some great lectures on this move of recursivity, the sense that that’s what makes a story, that recursivity, and as she says, at some point relatively early on a book/story stops being about the world and starts to be about the words that are down on the page so far). It starts to make meaning, but as I say, it’s more a poetic meaning, a meaning of rhyming scenes. Oh, and if you want to read a great essay about how short stories and novels use this kind of scene-rhyme, Charles Baxter has one in his book Burning Down the House that’s of use.

*

But though, as I’ve foregrounded, this is a book of fragmentary grief, told by a fragment collector (FC from here on out), there’s still an engine that drives the book forward. As we discussed at the outset of the semester, I think every novel, no matter how fragmentary—and if you want one that really pushes it, Rilke’s The Notebooks of Malte Laurids Brigge which Nunez references here a bunch pushes about as hard as any—does have an engine, or a thread, or a vanishing point, moving us forward through hundreds of pages. I suspect the vanishing point metaphor, like in a painting, works best for this one, and it’s kind of biological. It’s the question of Apollo’s death.

And it’s a genius way to move us along. Once FC takes on care of Apollo, no matter how fragmentary or meandering the book may seem, we know Apollo has only a year or two to live. We know Nunez has to deal with that fact. It’s weirdly at once a vanishing point that’s inside the frame of the painting (like in The Last Supper) and outside it. And as with that note about using the 1p, she states it directly in the book. “I have imagined it many times,” Nunez writes on p121. “How, among all the other questions certain to have come for you, was what will happen to the dog.”

It’s an ingenious little move.

What will happen to the dog? We want to know. It buys her so much space for the fragmentation, the introspection, the essayistic writing. Which is beautiful on its own terms, but which is in a novel. It gives us a finite temporal space to work in—look for this next week when we’re talking about Gatsby, where as a great Michael Chabon essay points out, is structured by the clear confines of a single summer: June, July, August. In the case of Apollo it’s the few years he has left. It’s complicated by the little metafictional move Nunez makes late. But she returns us to Apollo, and spares us the worst. It’s a beautiful ending of a beautiful book. By those final pages on the beach, I want to steal not just its fragments, but its whole.

First up: Mary Gaitskill’s THIS IS PLEASURE, a novella that was published by the New Yorker and then Pantheon. You can find it here:

Mary Gaitskill, THIS IS PLEASURE

https://www.newyorker.com/books/novellas/this-is-pleasure

Mary Gaitskill’s THIS IS PLEASURE

Our goal semester long has been to see what we can steal from the published novels we’re reading, to read them closely but always with it in mind: what can this novel tell me about the work I’m doing and will do down the road? And if there’s a progression of our readings on the syllabus, it’s with a special attention to structure. If there’s a thing that distinguishes the novel, or novella, or long story from the short story or poem (in addition to, you know, its being longer) it’s that in some ways it is defined by its shape. Novels are uniquely suited to making meaning out of shape, and structure, creating a framework on which all the beautiful prose can rest. As we said from semester’s start—if you want to write War and Peace, Bleak House, Middlemarch, the way to do it is to sit down and pound away for years. The question we’re asking here is: with a novel that hones to what I think of as a “short story aesthetic”—concise as possible; every word accounted for; an ending that shines a light back on what’s come before—how can it add that ingredient of structure to make it a book-length work.

The reason I wanted us to read This is Pleasure at this midpoint in the semester is because of how beautifully I think it takes up that challenge. Gaitskill is one of our most important short story writers and a masterful novelist (Veronica was a National Book Award finalist), and this book sits, teetering so precariously, on the edge of its form. When it was published in The New Yorker last summer they called it a “novella”; this Pantheon version we’re reading, bound between covers, is referred to in its subtitle as “a story.” But as with all the books we’ve read here, the length and shape of This is Pleasure grows organically from a series of structural decisions a master craftsperson has made. With We the Animals, it was so clearly a step forward for toeing the line between linked stories and a novel—124pp, short ending-oriented sections, each with a title. Housekeeping feels more like what we expect from a conventional novel, numbered sections that essentially function as chapters, following time’s arrow and focusing us on the quality of sentences and paragraphs that explode in the last third of the book into something wild, biblical even prophetic and wraithlike. I think Sula started to explode this a little formally—we move in an intentionally meandering fashion between points of view, but as we observed in class it’s really a kind of Flaubertian free indirect discourse she’s employing so beautifully, one we can always pin down and follow, but one that allows us moments of grace and epiphany—the best example being the late pages when we follow Sula right up to the moment of her death (or maybe past it).

For me anyway, the genius of This is Pleasure, and where I learn a ton about how to craft a novel/novella, is the decision to merge many of these structural moves, and to allow the narrative to grow organically out of a clear, finite, initial decision: two first-person POVs bouncing back and forth, one set off as “M.” for Margot, the other set off as “Q.” for Quin. That rule is established early and loudly, and while we suspect it’s well established by p6 on the first switch, it feels hard and fast by the move back to “M.” on p10. It’s simple but not at all facile, elegant without being showy. And it quickly subverts one large aspect of what we might expect from its subject matter—there’s a kind of overly reductionist, potentially cliched “he said she said” narrative we fear an accusation of sexual impropriety might lead to, and this isn’t that. It’s pointedly not that. It knows it could be that and doesn’t want to. Instead it’s “they each remember in their own complicated nuanced way” or something like that. As Chekhov famously said (paraphrasing here), My job as a writer is not to decide big questions (of God, morality, politics, etc.), but to reproduce as accurately as possible the way actual people think and talk. Something like that. Gaitskill is a very Chekhovian writer, in the best way, to great effect.

*

Anyway, at the risk of reading too closely, and becoming a critic rather than a novelist reading for what we might steal, I’d like to move a bit slowly through the first 20pp or so to point out what I think are some of the marvels of how Gaitskill makes this shape work. The first is just in looking at how interlocked she allows M and Q’s sections to be with some quick, useful language tics. To me the first of these comes on p7, when we learn that “Q.”’s full name is Quinlan M. Sanders. We pick up quickly that Quin is a nickname but buried in there is the fact that his middle initial is the same as Margot’s name—and typologically even more closely identical to Margot’s chapter headings. It ties their humanity together for us, creating an equivalency that will make it harder for Margot to dismiss him for his behavior, as it does for us by extension. Through a simple act of naming, Gaitskill binds us to seeing both Margot and Quin as intertwined. It also tunes our ear up to how closely we’ll want and need to read this book to access all it’s pleasures, but it does so in a relatively blatant way.

(Quick aside: we’ve talked a bunch about how adverbs are the least useful part of speech, and I set you up for the fact that Gaitskill, like Morrison, uses them well. Look at the two on p7: “The first thing was my nameplate, strangely affixed to the wall outside my office door, importantly announcing the existence of the now nonexistent QUINLAN M. SAUNDERS.” (itals mine). The “strangely” is good. The “importantly” is better, and so perfect. It’s an adverb we use incorrectly in speech all the time when we say, eg, “more importantly…”, a phrase that should go “more important.” “Importantly” means, instead, to do something with a sense of importance. (When we say “more importantly” it literally means, Man was she pretentious, and most of the time that’s not what we want to mean.) It’s a PERFECT description of Quin’s personality.

Note: Mary Gaitskill is very good at writing.

OK, back to it. The second big thing, and frankly it’s what I’d like to spend the rest of the time here on, is how subtly and masterfully Gaitskill enjambs the endings of Margot’s sections into the tops of Quin’s sections. It suggests a more deliberate shape, a more deliberate maker, who has built torrents of meaning into this short book. There’s a genius to the pattern of moving back and forth between M. and Q. Once we know that we’ll hit on relatively evenly length sections from each, it automatically doubles the size of the project, from within, organically, like the living organism it is. You could easily imagine the 40pp short story of This is Pleasure in Gaitskill’s hands only from Margot, or only from Quin. But this becomes a novella (or novella-ish thing) because of the pairing of these two voices.

And I think what I mean by enjambment is that they’re not he-said-she-said calls and responses— but they also don’t strictly follow time’s arrow in an easy-to-discern way—but they’re also not just juxtapositions, or placed at random. The endings of M.’s sections lead to the approach we’ll get to each of Q.’s. Let’s focus just on the shift on p 16 as our example so I can show what I mean:

We’re still in the early going here. We’ve just gotten a narrative of how Margot and Quin became friends, and she has given us this amazing revealing anecdote of seeing the private version of flamboyant Quin in a bodega, where without his knowing it, she sees him as “a funny man at the other end of the aisle, exploring his nose with a very large handkerchief” (what an arresting, telling image). But then, in the end of the section, we hear from Margot: “The next day, he sent me flowers and the friendship began.”

So much happens in such a small space here—Gaitskill has focused us on the conflict of public and private in Quin, the unique perspective she has on it. It’s done in a small collection of quick brushstrokes. But then we leap the divide to “Q.” and we see him handling the difficulty of the public and private: “I told Margot,” he begins, “and I told my brother; I did not tell my wife. Not at first… At first, the [law]suit was not against me but against the publishing house, and all she wanted was payment, which the company was prepared to make.”

This move establishes the shape of the whole rest of the book. You might go back and look at virtually any move between “M.” and “Q.” from the middle of the book to track it—each move doubles the size of the story by providing each of their POV, and each is linked in a similarly intricate fashion, like a jigsaw puzzle. You can easily imagine how you might mess with this pattern by adding another voice, moving to do something more like Sula (think of Morrison’s essay where she talks about adding that voice from “the man in the valley” at the start). There could be a preface, like Humbert’s lawyer in Lolita. This could be a 120pp book if you placed a “C.”=Carolina (Quin’s wife) section between each M and Q. You could add Sharona, his accuser, and it would quickly become a 180-200pp novel. Look at how quickly the shape—and meaning—would change.

But Gaitskill has the forbearance and authority to show us that’s not the story she’s telling here. The shape, the structure—and by extension but subordinate to the structure length—make the meaning of the book. Gaitskill is telling Margot and Quin’s stories (this is complicated by the fact that it’s very very very loosely a roman á clef, but we’re not going to get into that here). And I think I’d like to leave off here by noting the great effect she makes of it in what I feel is such a beautiful, moving ending.

We’re left with Quin, describing New York City. Mary was my thesis adviser up at Syracuse, and she taught a whole grad class on physical description. There’s a story in her collection Don’t Cry simply called “Description” (we won’t get into the fact that one of the characters is very loosely based on me, which makes me weirdly happy). And she is one of our great describers. She lends that talent, that power, to Quin at the end. In that last section, he begins by telling us: “Stories, it’s all stories. Life is too big for anybody and that’s why we invent stories.” All at once he’s hitting on bigger truths while he’s still deluding himself, telling himself a story of himself he’s made—and it’s problematic—but aren’t we all—and isn’t all wisdom also subterfuge—doesn’t Oscar Wilde have something on this topic—and—it’s very, very complicated. And then we just get the physical world, as Quin sees it, as only Mary Gaitskill can render it, Chekhovian and Nabokovian at once, and I’ll just leave you here with it again, because it’s so beautiful, and because only the structure that Gaitskill has crafted lands us there with such weight:

I walk in the street with tears running down my face; I walk in a world of sales racks and flavored refreshments, marching crowds, broken streets, and steam pouring through the cracks. Jackhammers, roaring buses, women striding into traffic, knifelike in their high, sharp heels, past windows full of faces, products, bright admonishments, light, and dust…

COMING UP:

Sigrid Nunez, THE FRIEND

Italo Calvino, INVISIBLE CITIES

F. Scott Fitzgerald, THE GREAT GATSBY + TRIMALCHIO (an early draft)

WG Sebald, THE EMIGRANTS